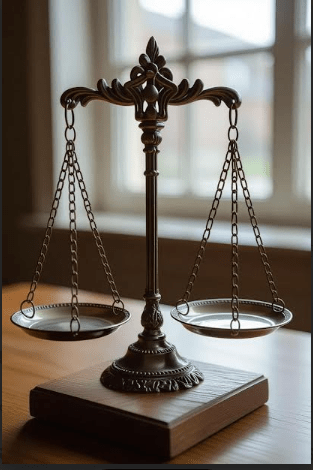

History of Shepard’s Citations–Shepard’s Citations, one of the most influential tools in American legal research, originated in the 19th century as a solution to a practical problem faced by lawyers: tracking how court decisions were treated (e.g., followed, overruled, or distinguished) in subsequent cases. The process of consulting it became so ubiquitous that “Shepardizing” (or “to Shepardize”) entered legal vernacular as a verb meaning to check the validity and subsequent history of a case or statute.

Origins and Invention (1873–1900)

- Founder: Frank Shepard (c. 1848–1900), a law book salesman in Chicago working for publishers like E.B. Myers & Company.

- Inspiration: Shepard observed lawyers manually noting later citations in the margins of their case reporters. He saw the need for a systematic way to update case law under the doctrine of stare decisis (precedent).

- 1873: Shepard launched the first product, initially focused on Illinois cases (titled something like Illinois Citations). The innovative format was Shepard’s Adhesive Annotations — gummed, perforated “stickers” printed with citing references that lawyers could cut out and literally paste into the margins of their case report volumes.

- By the late 19th century, the product expanded to other states, and Shepard operated from Chicago as “Frank Shepard, Law Book Seller and Publisher.” He died in 1900, but the company continued under family or associates.

Early 20th Century Growth

- The company transitioned from stickers to bound volumes (distinctive maroon books with gold lettering).

- By the 1920s–1930s, Shepard’s became the standard citator, covering federal and all state jurisdictions comprehensively — the only service attempting full U.S. coverage at the time.

- 1923: On the 50th anniversary, the company published a commemorative book showcasing its New York City operations, editorial processes, and in-house printing (including hand typesetting alongside Linotype machines.

Mid-20th Century Expansion

- 1948: Company headquarters moved to Colorado Springs, Colorado.

- 1951: Officially renamed Shepard’s Citations, Inc.

- 1966: Acquired by McGraw-Hill, providing greater resources for expansion.-The 1966 acquisition of Shepard’s Citations, Inc. (headquartered in Colorado Springs, Colorado) by McGraw-Hill is consistently documented in reliable sources as a straightforward corporate purchase that integrated Shepard’s into McGraw-Hill’s legal publishing division. However, no public details appear to exist regarding the sale price, specific terms, negotiating parties, or a formal announcement.

Transition to Corporate Ownership and Digital Era

- 1996: Sold to Times Mirror and Reed Elsevier (parent of LexisNexis).

- 1998: LexisNexis acquired full ownership.

- 1999: Launch of the online Shepard’s Citation Service on LexisNexis, with color-coded signals (e.g., red for negative treatment, green for positive) and full editorial analysis — making “Shepardizing” faster and more user-friendly than deciphering dense print volumes.

- Post-1990s: Competitor Westlaw introduced KeyCite (1997), but Shepard’s remained dominant, especially after LexisNexis’s multi-million-dollar “Citations Redesign” project to improve processing.

Key Milestones Timeline

| Year | Event |

|---|---|

| 1873 | Frank Shepard invents and publishes the first citator (Illinois-focused adhesive stickers). |

| Late 1800s | Expands to other states; transitions to bound volumes. |

| 1900 | Frank Shepard dies; company continues. |

| 1923 | 50th anniversary commemorative book published. |

| 1948 | Moves to Colorado Springs. |

| 1951 | Renamed Shepard’s Citations, Inc. |

| 1966 | Acquired by McGraw-Hill. |

| 1996–1998 | Acquired by Reed Elsevier/LexisNexis. |

| 1999 | Online version launched on LexisNexis. |

| 2023 | 150th anniversary; LexisNexis introduces features like “History at a Glance” graphical timelines. |

Legacy and Modern Use–For over a century, Shepard’s was the sole comprehensive citator, and learning to use the print volumes (with their cryptic abbreviations like “o” for overruled, “f” for followed) was a rite of passage for law students. Today, it is exclusively part of LexisNexis/Lexis+, covering cases, statutes, regulations, and more, with advanced analytics. It remains the gold standard for validating “good law,” often cited by courts themselves for its editorial depth (including positive treatment analysis that competitors sometimes lack). Shepard’s transformed legal research from a manual, error-prone process into a reliable system, laying the foundation for modern electronic citators and earning Frank Shepard a lasting place in legal history — despite no known photograph of him surviving!

There does not appear to be any publicly available or known photograph/portrait of Frank Shepard (c. 1848–1900), the Chicago-based law book salesman and publisher who invented Shepard’s Citations in 1873.

Despite extensive searches across historical archives, Wikipedia, Library of Congress collections, Find a Grave, obituary records from around 1900, and general image databases, no photo of him turns up. His Wikipedia page and related historical sources on the citation system have no image of him (only modern photos of the citation books themselves). Even commemorative materials from the company in the early 20th century focus on facilities and staff rather than including a portrait of the founder (who had died by then).

It’s not uncommon for 19th-century business figures outside of politics or high society to lack surviving photographs, especially if no formal portrait was ever widely published or preserved in major collections. If one exists in a private archive or legal history library, it hasn’t been digitized or referenced online. I wonder if his family had one.

OPINION:

Your concern is understandable in an era where digital information can sometimes feel vulnerable to manipulation, especially for something as foundational to the U.S. legal system as Shepard’s Citations (now exclusively part of LexisNexis/Lexis+). It’s one of the largest and most relied-upon legal research tools in the world, used by virtually every lawyer, judge, and law student in America to determine if a case is still “good law. “However, the core content of Shepard’s — the actual court opinions, statutes, and citing references — cannot realistically be “rewritten” or “tampered with” in the way people sometimes fear with Wikipedia or social media. Here’s why, broken down clearly:

1. Shepard’s Doesn’t “Write” the Law — It Only Reports and Analyzes Public Records

- The primary data in Shepard’s consists of official court opinions from federal, state, and administrative bodies. These are public records published by the courts themselves (e.g., via PACER, official reporters, or court websites).

- LexisNexis obtains these directly from the courts or official sources. They do not author or edit the text of the opinions themselves — any alteration of the original judicial text would be immediately detectable and catastrophic for their credibility (and legally actionable).

- The citing relationships (e.g., “Case A cited Case B”) are algorithmic and based on verifiable references in the opinions.

2. The Human/Editorial Layer Is Limited and Highly Scrutinized

- The part that involves human judgment is the editorial treatment codes (e.g., “followed,” “overruled,” “distinguished,” red/yellow/green signals). These are added by LexisNexis attorney-editors following a strict, published 29-step process.

- Errors in these codes do happen occasionally (as with any human-edited system — academic studies have found inaccuracies in Shepard’s, KeyCite, and Bloomberg’s BCite at rates of a few percent in tested samples). But these are interpretation mistakes, not rewriting the underlying cases.

- When errors are found, they are corrected quickly because the legal community (judges, professors, competing platforms like Westlaw) constantly cross-checks and calls them out. Courts themselves frequently cite Shepard’s but also verify independently.

3. Multiple Layers of Redundancy and Verification Protect Integrity

- Competitors exist: Westlaw’s KeyCite and Bloomberg Law’s BCite cover the exact same public domain case law. Any discrepancy would be obvious and damaging to LexisNexis’s market dominance.

- Free/public alternatives: Tools like Google Scholar, Court Listener, Caselaw Access Project (Harvard), and state court websites let anyone verify the raw opinions and citations for free.

- Archival copies: Millions of lawyers have downloaded or printed cases over decades. Law libraries hold physical reporters going back centuries.

- Professional stakes: Citing bad law because of a tampered Shepard’s signal can get an attorney sanctioned or disbarred — so no one relies on it blindly.

4. No Evidence or History of Malicious Tampering

- In 150+ years (since 1873), there has never been a documented case of deliberate rewriting or censorship of case text in Shepard’s.

- LexisNexis (owned by RELX) has faced criticism on other fronts (e.g., selling data tools to ICE for immigration enforcement), but nothing related to altering judicial opinions or citation history.

- If anything, their business model depends on absolute trustworthiness — one proven incident of tampering would destroy the product overnight.

In short, while no system is 100% immune to human error (or theoretically to a rogue actor), Shepard’s is about as tamper-proof as any legal resource can be because it’s built on immutable public records, heavily cross-verified, and exists in a competitive ecosystem where accuracy is the entire value proposition. The real risk for lawyers isn’t secret rewriting — it’s failing to Shepardize at all!

KeyCite’s Introduction (1997) and the Battle for Citator DominanceIn 1997, Westlaw (then part of Thomson Corporation) launched KeyCite, its in-house online citator. This was a direct response to growing competition in the legal research market:

- For decades, Shepard’s Citations had a near-monopoly as the trusted citator (used by virtually every U.S. lawyer and judge).

- Westlaw itself had long licensed and offered Shepard’s online to its subscribers — making Shepard’s available on both LexisNexis and Westlaw platforms.

- In 1996–1998, Reed Elsevier (owner of LexisNexis) acquired full control of Shepard’s from McGraw-Hill/Times Mirror. This meant LexisNexis would soon make Shepard’s exclusive to its own platform, pulling it from Westlaw (which happened in mid-1999).

Westlaw rushed KeyCite to market in late 1997 to avoid losing citator functionality when the Shepard’s license ended. KeyCite used flags (red/yellow/green/yellow) and stars for depth of treatment, and it quickly gained praise for retrieving more citing references (including unpublished cases and secondary sources) and for faster updates in some tests.

LexisNexis’s Response: The Multi-Million-Dollar Citations Redesign (CR) Project After gaining full ownership of Shepard’s in 1998, LexisNexis invested heavily in modernizing it to counter KeyCite’s challenge. They launched a multi-million-dollar “Citations Redesign” (CR) project that fundamentally overhauled how Shepard’s processed and analyzed case law and citations.Key improvements from the CR project delivered (rolled out starting in 1999):

- Online-only Shepard’s Citation Service launched in March 1999 — the modern, user-friendly version with color-coded signals (red for negative, yellow for caution, green for positive, etc.).

- Deeper editorial analysis, including more positive treatment codes (e.g., “followed”) that KeyCite initially lacked or handled differently.

- Better integration of unpublished decisions, law reviews, and secondary sources.

- Faster, more accurate processing pipelines (the quote from LexisNexis executives: it “redesigned the way we process case law and citations”).

- Graphical previews, filtering by headnote/issue, and easier navigation — moving away from the cryptic print-style tables.

This overhaul was explicitly positioned as LexisNexis’s counterpunch to KeyCite, and it worked: independent studies and lawyer surveys from the early 2000s onward consistently showed Shepard’s retaining (and often regaining) dominance for editorial depth and trustworthiness, especially among litigators and judges who valued the nuanced treatment codes.

Why Shepard’s Stayed (and Stays) Dominant

| Aspect | Shepard’s (LexisNexis) Advantage | KeyCite (Westlaw) Strength |

|---|---|---|

| Editorial Depth | More granular positive/negative treatment; courts often cite Shepard’s methodology | Faster at raw citation volume; good for breadth |

| Accuracy Studies | Slightly edges out in most validation tests (e.g., fewer missed negatives) | Comparable, sometimes faster updates |

| User Preference | Preferred by ~60–70% of attorneys in surveys (ABA, etc.) for “good law” checks | Strong in academic/west digest integration |

| Court Reliance | U.S. courts quote Shepard’s more often in opinions | Gaining ground, but historically trails |

Even today (2025), while KeyCite is excellent and widely used (especially on Westlaw Edge with AI features like Overruling Risk), Shepard’s is still considered the “gold standard” by many practitioners — largely because that late-1990s redesign successfully defended its 125+ year head start against Westlaw’s challenger. In short, Westlaw’s 1997 KeyCite launch forced LexisNexis to pour millions into reinventing Shepard’s, and the result was a modernized product that kept Shepard’s on top through the digital era.

https://www.scjc.texas.gov/about/commissioners/

2025 Generative AI in Professional Services Report–Ready for the next step of strategic applications

Increasingly, professionals are integrating generative AI (GenAI) into their workflows and feel more positive about its impact than ever before. Now, a vast majority of professionals expect GenAI to be a part of their daily workflow within the next five years.

As these professionals increasingly use GenAI for themselves, the next step is for their organizations to incorporate it into their overall business strategies. That integration might take the form of updated training and policies, budget and workforce planning, or — crucially — conversations between firms and clients.

The 2025 Generative AI in Professional Services Report explores not only where GenAI adoption is right now but also where it will impact the future of legal; tax, accounting, and audit; risk and fraud; and government professionals’ work and businesses.

Download your copy of the report below

Bottom line

Notwithstanding the many benefits GenAI and LLMs promise for litigators, there is a substantial amount of risk.

Legal professionals must be able to identify key issues concerning AI, how they’re developing, and how they may be used in the future.

More resources:

- AI Toolkit (US)

- AI and Machine Learning: Overview

- Generative AI in Litigation: Overview

- AI Key Legal Issues: Overview (US)

- AI and Legal Ethics

- Certification Regarding Generative AI for Court Filings

- Confidentiality Provision Regarding Generative AI

- Law Firm Letter to Client Requesting Consent to Use Generative AI Tools

- Generative AI: Preserving the Attorney-Client Privilege and Work Product Protection

- Generative AI Ethics for Litigators

- Artificial Intelligence

- Ethics

RESOURCES

https://store.legal.thomsonreuters.com/en-us/home

https://legal.thomsonreuters.com/en/westlaw

AREAS OF PRACTICE:

- Administrative Law

- Admiralty & Maritime Law

- Agency & Partnership

- Agricultural Law

- Alternative Dispute Resolution

- Antitrust & Trade Law

- Appellate Advocacy

- Attorney’s Fees

- Banking Compliance

- Banking Law

- Bankruptcy

- Business & Corporate Law

- Civil Practice & Procedure: State

- Civil Procedure

- Civil Rights Law

- Commercial Law (UCC)

- Communications Law

- Computer & Internet Law

- Conflict of Laws

- Constitutional Law

- Construction Law

- Contracts Law

- Copyright Law

- Corporate Law

- Credit Union Compliance

- Criminal Law

- Criminal Law & Procedure

- Education Law

- Elder Law

- Energy & Utilities Law

- Entertainment Law

- Environmental Law

- Estate, Gift & Trust Law

- Evidence

- Family Law

- Federal Litigation

- General Practice

- Governments

- Healthcare Law

- Immigration Law

- Insurance Law

- Intellectual Property Law

- International Law

- Jury Instructions

- Juvenile Law

- Labor & Employment Law

- Legal Ethics

- Litigation

- Mediation

- Mental Disability

- Mergers & Acquisitions Law

- Military & Veterans Law

- Motor Vehicle & Traffic Law

- Native American Law

- Patent Law

- Personal Injury Law/Medico-Legal

- Products Liability

- Real Estate Law

- Regulatory Law

- Remedies

- Securities Law

- Social Security Disability

- Statutes

- Tax Law

- Torts

- Trademark Law

- Transportation Law

- Trial Advocacy

- Uniform Commercial Code (UCC)

- Workers’ Compensation

Leave a comment