### Overview

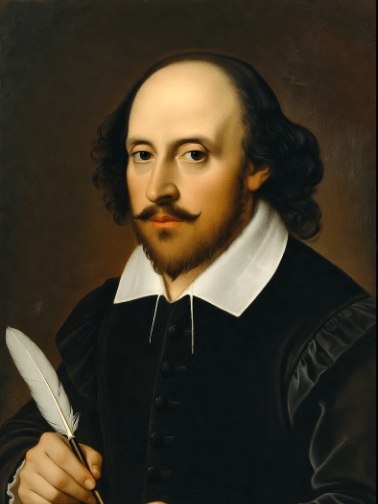

of *A Shakespearian Grammar* by E.A. Abbott *A Shakespearian Grammar: An Attempt to Illustrate Some of the Differences Between Elizabethan and Modern English* is a seminal 1870 reference work (revised and enlarged in subsequent editions, such as the third in 1886) by Edwin Abbott Abbott (1838–1926), a British educator, theologian, and author best known for his satirical novella *Flatland*.

Written during Abbott’s tenure as headmaster of the City of London School, the book serves as a comprehensive guide to the syntactic, idiomatic, prosodic, and phonetic peculiarities of Elizabethan English as found in Shakespeare’s works. Its primary purpose is educational: to help students, teachers, readers, scholars, and editors navigate subtle grammatical “irregularities” that glossaries alone can’t explain, preventing misinterpretations of Shakespeare’s text. Abbott argues that Elizabethan English was a transitional language—flexible, vigorous, and experimental—shaped by the loss or retention of Anglo-Saxon inflections, classical influences (Latin, Greek), and a preference for brevity and clarity over rigid symmetry.

He treats English with the same rigor as ancient languages, drawing on a full re-reading of Shakespeare’s canon (plays, sonnets, poems like *Venus and Adonis*) and contemporaries (e.g., Spenser, Jonson, the King James Bible). Abbott emphasizes that what modern readers see as “errors” (e.g., double negatives, pronoun confusions) are often deliberate for euphony, meter, rhetoric, or dramatic effect.

The book resolves textual ambiguities without emending originals and promotes studying English as preparation for classics. Influences include German grammarian Eduard Matzner and scholars like Frederick Furnivall and Richard Morris. It’s praised for its readability and exhaustiveness, covering every idiomatic usage in Shakespeare, though some critics note its Victorian lens. ###

Structure and Key Topics The book is organized for quick reference, with over 500 numbered paragraphs (PAR. 1–515+), cross-references, etymologies, and comparisons to other languages (e.g., French, Danish).

Examples are cited by play/act/scene/line (e.g., *Hamlet* i. 2. 77) from early editions like the Folio. It includes abbreviations for plays (e.g., A.Y.L. for *As You Like It*, J.C. for *Julius Caesar*) and covers works from *Comedy of Errors* to *The Tempest*. – **Prefaces and Introduction (pp. 1–16)**:

Discuss the book’s scope, revisions (third edition tripled in size with full indexes for select plays), and Elizabethan English’s “laws” (e.g., “thou” for intimacy or insult vs. “you” for respect). Explains causes of differences: inflectional shifts, “division of labor” in word meanings (e.g., prepositions like “by” gaining specificity), pronunciation variations, and metaphorical evolutions (e.g., “exorbitant” from “out of orbit” to “excessive”). – **Grammar (Core Section, pp. 17–400+)**: Divided by parts of speech and syntax.

Key topics include: | Part of Speech | Key Discussions and Examples

**Adjectives (PAR. 1–22)** | Used as adverbs (e.g., “raged more fierce” – *Richard II* ii. 1. 173); double comparatives/superlatives (e.g., “more larger” – *Antony and Cleopatra* iii. 6. 76; “most unkindest” – *Julius Caesar* iii. 2. 187); pleonastic forms (e.g., “most best” – *Twelfth Night* iii. 4. 375); archaic senses (e.g., “awful” = “awe-struck” – *Macbeth* ii. 3. 2). | |

**Adverbs (PAR. 23–76)** | Forms without -ly (e.g., “fastly” – *Lucrece* 9); prefixes like a- (e.g., “a-hungered”); emphatic placements causing inversion (e.g., “Seldom he smiles” – *Julius Caesar* i. 2. 205); special uses (e.g., “anon” = “immediately”; “presently” = “at once”; “even” = “just now” – *Merry Wives of Windsor* iv. 5. 26). | |

**Articles (PAR. 77–94)** | Omission for poetic/archaic effect (e.g., “glorious Christian field” – *Richard II* iv. 1. 93); insertion after adjectives (e.g., “poor a thousand pounds” – *As You Like It* i. 1. 2); “the” with verbals (e.g., “the leaving it” – *Macbeth* i. 4. 8). | |

**Conjunctions (PAR. 95–137)** | “But” = “except/unless” (e.g., “No man but hates me” – *Measure for Measure* v. 1. 237); “as” = “if/that” (e.g., “As ’twere a careless trifle” – *Macbeth* i. 4. 11); doublings/transpositions (e.g., “and if” = “even if”). | |

**Prepositions (PAR. 138–204)** | Metaphorical/local shifts (e.g., “after” = “according to” – *Coriolanus* ii. 3. 288; “at” rejecting adjectives, e.g., “at friend” – *Winter’s Tale* v. 1. 140); archaic prefixes (e.g., “a-building” for “in building”). |

Later sections cover nouns (e.g., collective uses, genitives), pronouns (e.g., “ye” vs. “you,” relative omissions), verbs (e.g., infinitives without “to,” subjunctives for conditionals like “Were I crown’d” – *Richard II* iii. 2. 157), and syntax (e.g., double negatives for emphasis: “Nor never” – *Henry V* iv. 1. 287). – **Prosody (pp. 400+)**: Analyzes meter, accents, elisions (e.g., “o’er” for “over”), and rhymes; revised with input from phonetician A.J. Ellis. – **Appendices and Indexes**: Word indexes, play-specific references, and errata. ###

Availability and Legacy The book remains a standard resource for Shakespeare studies, available in affordable reprints (e.g., Dover edition for $7.99) and free digital scans.

You can read the full PDF online via Princeton’s open-access repository: [Download here](http://commons.princeton.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/41/2017/09/Abbott-A-Shakespearian-Grammar.pdf).

Or access it on Archive.org for borrowing.

Leave a comment